Post outline

Introduction

Welcome back to yet another year of the TheZZAZZGlitch’s April Fools event, and this blogs obligatory yearly post! This event was smaller than previous years, while still maintaining the usual charm and creativity of the challenge design from the previous years.

Due to real-life time constraints, I don’t have much time to prepare this post, so unfortunately I won’t be able to explain stuff as in-depth as in the previous years. As such, this writeup will mostly be a more direct explanation of how I arrived at the solution rather than the usual step-by-step walkthrough of each challenge. I’ll still try to make this as easy to understand as possible for anyone who wishes to learn the ancient arts of Glitchology (well, mainly CTF solving, I guess).

You can find the event save file on the official site here, however the event has already concluded so you won’t be able to submit scores.

As usual, you can find my tools, notes and other misc stuff in the muzuwi/fools25 repository. It contains the bruteforcer for challenge #3 and other scripts reimplementing parts of the blob generation and RNG used during it.

Challenge #1 - Get the Gem!

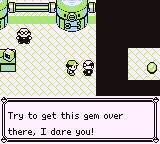

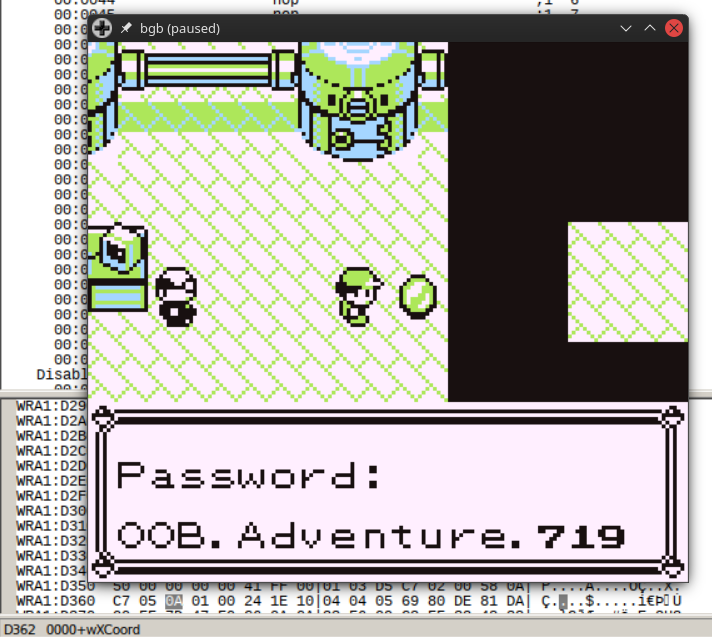

The first challenge is to reach and interact with a gem in Bill’s House. The challenge NPC tells us:

The simplest approach would be to walk-through-walls to reach the gem, however there’s two problems with this approach:

1) The save file has a form of anti-cheat, and commonly used walk-through-walls methods are blocked.

This one is actually relatively easy to work around if you have access to a debugger; by breaking at 00:0C0C, attempting

to walk through a solid and clearing the carry flag once the break hits, you can walk through a single tile. However…

2) The gem is actually located outside of the regular map bounds. Attempting to walk through walls to it will just result

in a rst 38 crash.

Main map of Bill’s house

Main map of Bill’s house

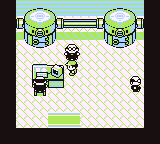

The gem lays out of bounds

The gem lays out of bounds

Checking D368 and D369, we can verify that indeed the actual map size is:

-

D368/wCurMapHeight=0x4blocks (a block is 2x2 in-map tiles) -

D369/wCurMapWidth=0x4blocks

We don’t have to WTW though, as the in-map player position is stored at D361 (wYCoord) and D362 (wXCoord).

We can manipulate the values and place the player immediately to the left of the gem sprite.

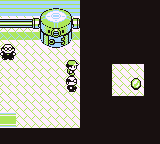

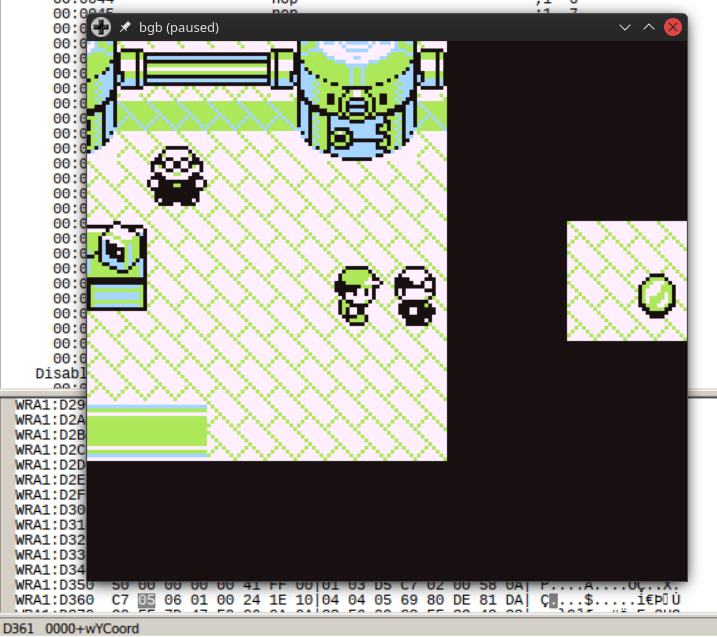

Checking player X/Y position right next to the NPC

Checking player X/Y position right next to the NPC

We can modify the player’s X position and add 4 tiles to the current position relative to the tile immediately to the left of the NPC.

Afterwards, it is possible to interact with the gem by pressing A:

Modifying the player X coordinate and interacting with the gem

Modifying the player X coordinate and interacting with the gem

Challenge #2 - A code to surpass all others

This next challenge directly targets the unlock code functionality used to track progression in the save file and for scoring on the event’s website.

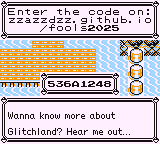

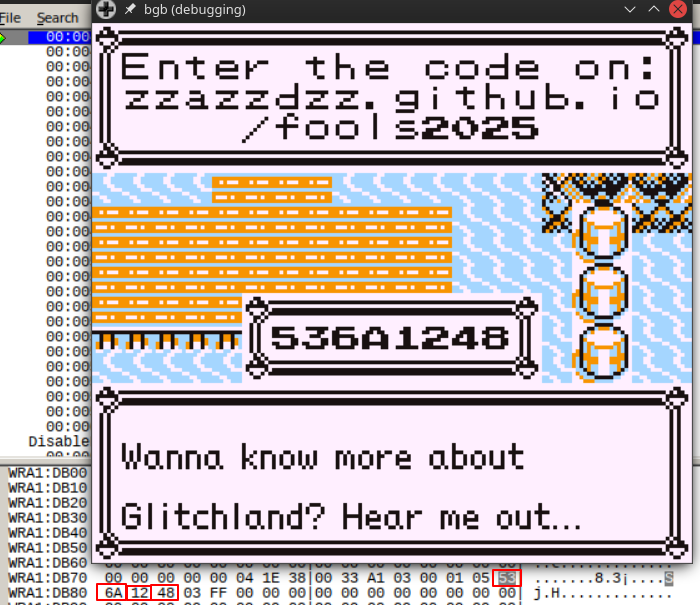

An example unlock code

The challenge NPC gives us a hint that there’s a single unused unlock code that we’re meant to find.

Unlock code generation

I would love to explain my very robust process of identifying the routine responsible for generating the unlock codes, but in reality I simply scrolled around for a bit in bgb until I was able to find the actual location of the unlock code in WRAM:

This was made incredibly easy by the fact the unlock code has a generation animation, so it’s trivial to locate the four bytes in memory that are changing as the unlock code changes.

Afterwards, I set a few breakpoints on the location involved and got to reversing knowing that the 32-bit completion code is placed by something at DB7F.

The most interesting hit was at 02:A9B1, and in the end it lands us in the function responsible for calculating the unlock code and displaying it on screen, along with the fancy byte-shuffling animation for it.

At this point, I imported a memory dump of the whole memory state into Ghidra for easier reverse-engineering.

I personally used GhidraBoy for this, but I had to make some changes to the default memory map it generates to just map the whole dump from start to end of the address space.

Here’s the decompiled version as seen by Ghidra, with some labels for standard ROM functions added by me:

void PrintCompletionCodeForSecretValue(byte secret_value)

{

uint8_t uVar1;

char outer_count;

char inner_count;

byte *pbVar2;

byte *ptr;

outer_count = PossiblyAnotherChecksum(0xb95f);

if (outer_count == -0x15) {

DAT_cfc9 = 6;

DAT_cfc8 = 6;

DAT_cfc7 = 0xff;

DelayFrames(0xeb);

COMPLETION_CODE[0] = 0;

COMPLETION_CODE[1] = 0;

COMPLETION_CODE[2] = 0;

COMPLETION_CODE[3] = 0;

TextBoxBorder((void *)0xc459,0x108);

UpdateSprites();

ptr = &UNK_1f3c + (uint)secret_value * 3;

outer_count = '\x14';

do {

pbVar2 = COMPLETION_CODE;

inner_count = '\x04';

do {

*pbVar2 = *pbVar2 ^ *ptr;

pbVar2 = pbVar2 + 1;

ptr = ptr + 1;

inner_count = inner_count + -1;

} while (inner_count != '\0');

FUN_a05d(0xc46e);

uVar1 = PlaySound(0xab);

DelayFrames(uVar1);

outer_count = outer_count + -1;

} while (outer_count != '\0');

PlaySound(0x89);

uVar1 = WaitForSoundToFinish();

DelayFrames(uVar1);

PlayDefaultMusic();

TextBoxBorder(&DAT_c3a0,0x312);

UpdateSprites();

uVar1 = CopyData(0xaa3e,0x37,0xc3b4);

DelayFrames(uVar1);

return;

}

DAT_d163 = 0x49;

DAT_cbbe = CONCAT11(0xca,DAT_ff04);

CopyData(0xb050,0x14);

return;

}

The most important part is that the function expects a parameter in the A register, based on which a different unlock code is generated every time.

I verified this to be the case by attempting to change the value and seeing whether a flag given by an NPC changes afterwards.

Using the nostalgic NPC in Vermilion City, I observed that the passed in parameter is 02, and changing this value to anything else caused a different code to be generated:

Original state of the

Original state of the A register is 02 at the time of jump to 02:A9B1

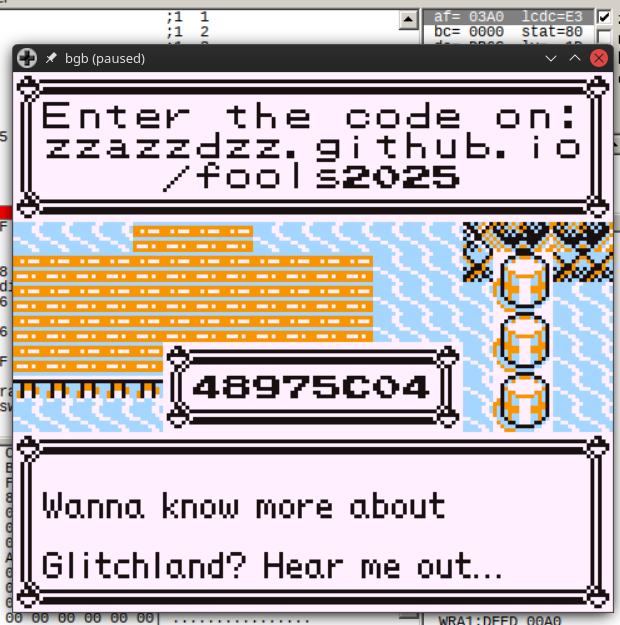

Changing

Changing A register to be 03 instead causes a different unlock code to be generated (see above: the code was previously 536A1248). Note that this change needs to be done before the push af instruction is executed.

The secret value that affects which code is generated can have 256 possible values, so it could take a bit of time to generate them all and test them one by one on the challenge website but it would probably be feasible.

We don’t have to resort to brute forcing quite yet though, as the NPC hints that the code is just one above the rest!.

Using Ghidra, I was able to easily cross-reference different places in the dumped memory that also jump into the unlock code generation function.

They all belonged to the scripts of different flag-giving NPCs, and all of them had a unique value loaded into the A register before calling to display the correct code:

3e 0c LD A,0xc

c3 b1 a9 JP PrintCompletionCodeForSecretValue

3e 07 LD A,0x7

c3 b1 a9 JP PrintCompletionCodeForSecretValue

3e 0a LD A,0xa

c3 b1 a9 JP PrintCompletionCodeForSecretValue

3e 0b LD A,0xb

c3 b1 a9 JP PrintCompletionCodeForSecretValue

Finding the right secret value

Using the fact that all of the NPC scripts will have the same byte sequence to jump to the code generation, I could then search for the C3 B1 A9 byte sequence in bgb while revisiting past NPCs.

By noting down all possible values the A register is loaded with right before the jumps, I was able to create a list of secret values used by NPCs to generate valid unlock codes.

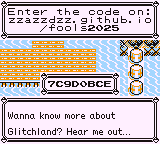

With this, it was only a matter of generating an unlock code for a secret value that is just one above the highest value in that list.

The final secret value, one above the others, is 0x17, and the code generated for it is:

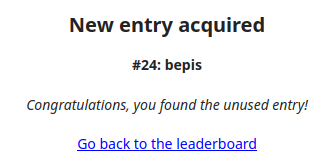

Submitting the code on the challenge site confirms this is the one:

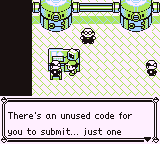

Challenge #3 - Password

The final challenge involves reverse-engineering the correct password to give to an NPC.

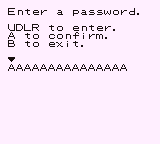

The password entry itself requires you to provide a 15-character password:

Only lower-case and upper-case alphanumeric, along with the ! and ? characters are allowed for entry.

Finding validation routines

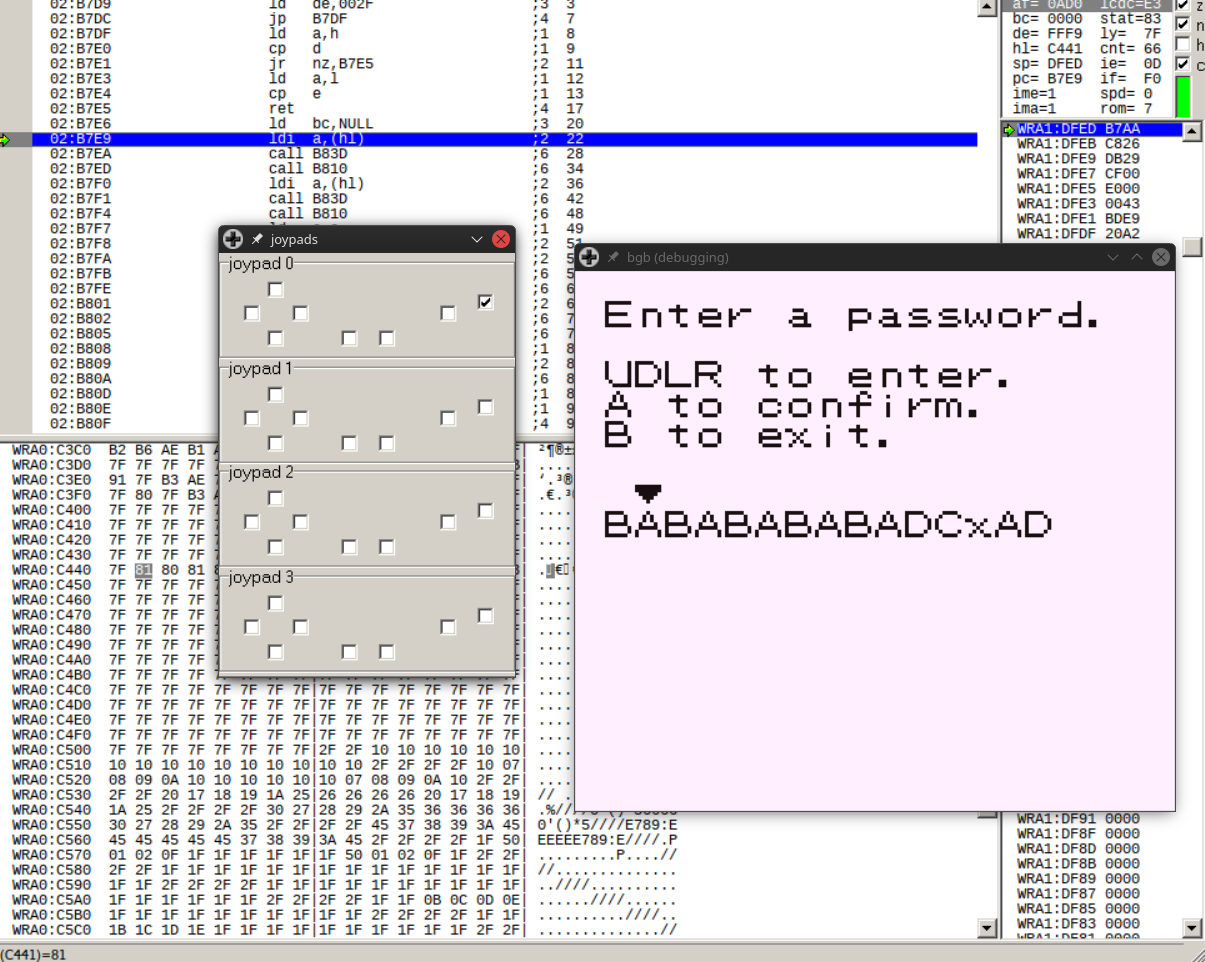

To find the code responsible for password validation, I set the password to a predictable pattern and then used the power of randomly scrolling through bgb until I come across something that looks vaguely like the pattern I set.

The password is stored in the typical charset used by the Gen 1 engine, and is stored starting at C441.

Setting a read breakpoint here will have a lot of hits, as it is read on every frame while rendering the password entry dialogue.

After skipping over the irrelevant hits related to rendering (bgb’s Joypad window help with accepting the password here), we finally arrive at a routine at 02:B7E9.

At this point, I once again chose to use Ghidra for reverse-engineering and imported a dump of memory created from bgb (File > save memory dump) for further analysis.

Reverse engineering password validation

The breakpoint landed us in 02:B7E9, but this is only a leaf function from the main password validation method.

The actual starting point of the password validation logic is at 02:B7A4 and consists of multiple calls to similar functions but with different arguments.

We can also see that at HL is loaded at three different points, with addresses pointing to groups of 5 characters of the password that was entered:

PasswordCheck

b7a4 21 41 c4 LD HL,0xc441

b7a7 cd e6 b7 CALL ConsumeRawInput5 input_t ConsumeRawInput5(byte *

b7aa 7d LD A,L

b7ab e6 07 AND 0x7

b7ad c0 RET NZ

b7ae cd b5 b6 CALL CallGeneratedBlobAtOffset uint16_t CallGeneratedBlobAtOffs

b7b1 11 aa ad LD DE,0xadaa

b7b4 cd df b7 CALL CompareU16 void CompareU16(uint16_t param_1

b7b7 c0 RET NZ

b7b8 21 46 c4 LD HL,0xc446

b7bb cd e6 b7 CALL ConsumeRawInput5 input_t ConsumeRawInput5(byte *

b7be 7d LD A,L

b7bf e6 07 AND 0x7

b7c1 c0 RET NZ

b7c2 cd b5 b6 CALL CallGeneratedBlobAtOffset uint16_t CallGeneratedBlobAtOffs

b7c5 11 39 ac LD DE,0xac39

b7c8 cd df b7 CALL CompareU16 void CompareU16(uint16_t param_1

b7cb c0 RET NZ

b7cc 21 4b c4 LD HL,0xc44b

b7cf cd e6 b7 CALL ConsumeRawInput5 input_t ConsumeRawInput5(byte *

b7d2 7d LD A,L

b7d3 e6 07 AND 0x7

b7d5 c0 RET NZ

b7d6 cd b5 b6 CALL CallGeneratedBlobAtOffset uint16_t CallGeneratedBlobAtOffs

b7d9 11 2f 00 LD DE,0x2f

b7dc c3 df b7 JP CompareU16 void CompareU16(uint16_t param_1

The main function essentially:

- Performs some operations on a group of 5 characters, then checks whether the results lowest 4 bits are zero before proceeding.

- Calls a different function with the previous result, and checks the 16-bit value returned in

DEagainst hardcoded constants.

This is done in isolation for each of the three groups of 5 characters, at which point the function returns, presumably to print a success message.

The fact that the password actually consists of 3 independent groups significantly reduces the search space we’ll need to traverse when searching for the correct password. For now, let’s focus on the first operation - the one that actually transforms what we input into the password dialogue.

input_t __asm ConsumeRawInput5(byte * input)

b7e6 01 00 00 LD BC,0x0

b7e9 2a LD A,(HL+)

b7ea cd 3d b8 CALL PokeCharToNumericInteger byte PokeCharToNumericInteger(ch

b7ed cd 10 b8 CALL MixBytes uint16_t MixBytes(uint16_t state

b7f0 2a LD A,(HL+)

b7f1 cd 3d b8 CALL PokeCharToNumericInteger byte PokeCharToNumericInteger(ch

b7f4 cd 10 b8 CALL MixBytes uint16_t MixBytes(uint16_t state

b7f7 59 LD E,C

b7f8 0e 00 LD C,0x0

b7fa 2a LD A,(HL+)

b7fb cd 3d b8 CALL PokeCharToNumericInteger byte PokeCharToNumericInteger(ch

b7fe cd 10 b8 CALL MixBytes uint16_t MixBytes(uint16_t state

b801 2a LD A,(HL+)

b802 cd 3d b8 CALL PokeCharToNumericInteger byte PokeCharToNumericInteger(ch

b805 cd 10 b8 CALL MixBytes uint16_t MixBytes(uint16_t state

b808 51 LD D,C

b809 2a LD A,(HL+)

b80a cd 3d b8 CALL PokeCharToNumericInteger byte PokeCharToNumericInteger(ch

b80d 68 LD L,B

b80e 67 LD H,A

b80f c9 RET

MixBytes

b810 cb 31 SWAP C

b812 57 LD D,A

b813 e6 0f AND 0xf

b815 81 ADD C

b816 4f LD C,A

b817 cb 20 SLA B

b819 cb 20 SLA B

b81b 7a LD A,D

b81c cb 37 SWAP A

b81e e6 03 AND 0x3

b820 80 ADD B

b821 47 LD B,A

b822 c9 RET

Each input character (which will be using the Gen 1 character map) is:

- Converted into an integer index using a predefined lookup table

- Mixed together using some shifts and swaps (I haven’t actually figured out what this does)

The last character is not mixed with anything else, but its index is used directly.

This function returns two 16-bit values: one in register HL containing the final result after going through all of the bytes, and one in register DE just after the first two bytes are processed.

Both values are used in the main password validation function as arguments to other functions.

The Blob

After performing all of that input shuffling, a different function at 02:B6B5 is called with the result of the operations in DE and HL.

This function stores the 16-bit value of HL + 0xA000 starting at address DB55, while preserving DE and calling a different function that is suspiciously close in memory (DB4A) to the address we’ve just modified.

This is (kind of) self-modifying code - however, it is relatively tame.

The goal of the modification is to change the CALL instruction to redirect it to a different address starting from A000, using the HL parameter as a relative offset.

CallGeneratedBlobAtOffset

b6b5 7c LD A,H

b6b6 e6 e0 AND 0xe0

b6b8 20 11 JR NZ,LAB_b6cb

b6ba d5 PUSH DE

b6bb 11 00 a0 LD DE,0xa000

b6be 19 ADD HL,DE

b6bf 11 55 db LD DE,0xdb55

b6c2 7d LD A,L

b6c3 12 LD (DE=>blobCallOffset[0]),A

b6c4 13 INC DE

b6c5 7c LD A,H

b6c6 12 LD (DE=>blobCallOffset[1]),A

b6c7 d1 POP DE

b6c8 c3 4a db JP CallGeneratedBlob uint16_t CallGeneratedBlob(undef

LAB_b6cb

b6cb 21 69 69 LD HL,0x6969

b6ce c9 RET

...

CallGeneratedBlob XREF[1]: CallGeneratedBlobAtOffset:b6c8(c

db4a 01 00 00 LD BC,0x0

db4d 21 00 00 LD HL,0x0

db50 af XOR A

db51 cd 98 da CALL SwitchBanksN void SwitchBanksN(byte bank)

blobCallOffset[0] (db54+1) XREF[0,2]: CallGeneratedBlobAtOffset:b6c3(W

blobCallOffset[1] (db54+2) CallGeneratedBlobAtOffset:b6c6(W

db54 cd 00 a0 CALL FUN_a000 undefined FUN_a000()

db57 c3 96 da JP SwitchBanks2 void SwitchBanks2(void)

Contents of A000:BFFF are generated at runtime (it is running from SRAM, so it needs to regenerate itself or risk corruption), but thankfully they are static and do not depend on the actual password input.

This is what I’ll refer to as The Blob, and it looks like this:

LAB_a000

a000 0e d6 LD C,0xd6

a002 09 ADD HL,BC

a003 15 DEC D

a004 c8 RET Z

a005 1d DEC E

LAB_a006+1

a006 20 38 JR NZ,LAB_a040

a008 0e b3 LD C,0xb3

a00a 09 ADD HL,BC

a00b 15 DEC D

a00c c8 RET Z

a00d 1d DEC E

LAB_a00e+1

a00e 20 68 JR NZ,LAB_a078

a010 0e ba LD C,0xba

a012 09 ADD HL,BC

a013 15 DEC D

a014 c8 RET Z

a015 1d DEC E

a016 20 50 JR NZ,LAB_a068

a018 0e d7 LD C,0xd7

a01a 09 ADD HL,BC

a01b 15 DEC D

a01c c8 RET Z

a01d 1d DEC E

a01e 20 48 JR NZ,LAB_a068

a020 0e a5 LD C,0xa5

a022 09 ADD HL,BC

a023 15 DEC D

a024 c8 RET Z

a025 1d DEC E

a026 20 00 JR NZ,LAB_a028

... continued until 0xBFFF ...

It consists of many repeated and similar-looking blocks of code, each located 8 bytes apart from each other.

I assume this is also the reason why an explicit check is made earlier whether HL is 8-byte aligned, as otherwise the jump would occur into the middle of a block which could break whatever it is trying to do.

The Blob directly depends on the DE value passed into it via register, which comes directly from the earlier input processing functions, and HL is explicitly zeroed out on entry (but it is used for determining the starting point of execution in The Blob via code modification).

I did not have it in me to reverse engineer what operation The Blob is actually doing, and simply treated it as a black box.

However, I’m curious whether this operation can be implemented more efficiently than emulating the GameBoy (it probably can, but it currently eludes me).

Forcing the password

Knowing the mechanisms behind the password validation, I could now reimplement it entirely and check if there’s a way to perhaps solve for the password more intelligently. However, the latter part did not happen as I found that naively brute forcing all possible five character password inputs is sufficiently fast enough.

The operations performed on the input password are simple enough and can be directly translated into C++.

Here, I chose to represent the input 5-byte character group within a single uint64 value, with the first byte of the input stored as the fifth byte of the uint64 and the following input bytes are consecutive lower bytes of the uint64.

struct ConsumeState {s

uint16_t hl;

uint16_t de;

};

constexpr uint16_t MixBytes(uint16_t state, uint8_t input) {

const uint8_t hi = ((input >> 4) & 0x3) + ((state >> 8)) * 4;

const uint8_t lo =

((input & 0xF) + (((state << 4) & 0xF0) | ((state & 0xF0) >> 4)));

return (static_cast<uint16_t>(hi) << 8) | lo;

}

constexpr ConsumeState ConsumeInput(uint64_t input) {

const uint8_t b0 = (input >> 32) & 0xFF;

const uint8_t b1 = (input >> 24) & 0xFF;

const uint8_t b2 = (input >> 16) & 0xFF;

const uint8_t b3 = (input >> 8) & 0xFF;

const uint8_t b4 = input & 0xFF;

uint16_t acc = 0;

acc = MixBytes(acc, POKE_CHAR_IDX_LOOKUP[b0]);

acc = MixBytes(acc, POKE_CHAR_IDX_LOOKUP[b1]);

const uint8_t v0 = acc & 0x00FF;

acc = acc & 0xFF00;

acc = MixBytes(acc, POKE_CHAR_IDX_LOOKUP[b2]);

acc = MixBytes(acc, POKE_CHAR_IDX_LOOKUP[b3]);

const uint8_t v1 = acc & 0x00FF;

const uint16_t de = (v1 << 8) | v0;

const auto idx = POKE_CHAR_IDX_LOOKUP[b4];

const uint16_t hl = (idx << 8) | ((acc >> 8) & 0xFF);

return ConsumeState{

.hl = hl,

.de = de,

};

}

POKE_CHAR_IDX_LOOKUP is a premature optimization using a lookup table that maps bytes to the correct integer index as calculated in the save file, but it could very well be directly translated into an array with a loop, just as the save file does.

The output of ConsumeInput, as we’ve seen above, is then used to:

1) HL: determine the starting point of execution in The Blob

2) DE: passed directly to The Blob

To calculate the result of executing The Blob (I will keep using this name), I went with the least-effort approach of implementing a minimal LR35902 instruction set emulator that only implements the required opcodes that are contained within the A000:BFFF area.

struct EmuState {

uint16_t pc{};

uint16_t hl{};

uint8_t b{};

uint8_t c{};

uint8_t d{};

uint8_t e{};

bool zero{};

bool terminated{};

};

constexpr uint16_t ExecuteBlob(uint16_t offset, uint16_t init_de) {

if (offset & 0xE000) {

return 0x6969;

}

EmuState d;

d.d = init_de >> 8;

d.e = init_de & 0xFF;

d.pc = offset;

while (!d.terminated) {

const uint8_t op = BLOB[d.pc++];

switch (op) {

case 0x0E: {

d.c = BLOB[d.pc++];

break;

}

case 0x09: {

d.hl += (d.b << 8) | d.c;

break;

}

case 0x15: {

d.d -= 1;

d.zero = d.d == 0x0;

break;

}

case 0x18: {

const int8_t offset = static_cast<int8_t>(BLOB[d.pc++]);

d.pc += offset;

break;

}

case 0x1D: {

d.e -= 1;

d.zero = d.e == 0x0;

break;

}

case 0x20: {

const int8_t offset = static_cast<int8_t>(BLOB[d.pc++]);

if (!d.zero) {

d.pc += offset;

}

break;

}

case 0xC8: {

d.terminated = d.zero;

}

default: {

continue;

}

}

}

return d.hl;

}

Amusingly, all of the basic functions are actually constexpr, which helped greatly while reimplementing them as I could do static_assert-driven development like so:

static_assert(ConsumeInput(0x8180818081).hl == 0x100, "self-test #0.hl failed");

static_assert(ConsumeInput(0x8180818081).de == 0x1010,

"self-test #0.de failed");

static_assert(ConsumeInput(0x8687FEFBE7).hl == 0x3F0F,

"self-test #1.hl failed");

static_assert(ConsumeInput(0x8687FEFBE7).de == 0xC967,

"self-test #1.de failed");

static_assert(ExecuteBlob(0, 0) == 0x1a51, "self-test #2 failed");

static_assert(ExecuteBlob(0x1ff8, 0) == 0x9647, "self-test #3 failed");

Checking an input then becomes a matter of calculating the DE and HL values for it, evaluating The Blob using these two values, and checking whether the final value is one of the hardcoded constants for each input character group:

- Group 1:

0xADAA - Group 2:

0xAC39 - Group 3:

0x002F

void CheckInput(uint64_t input) {

const auto state = ConsumeInput(input);

if (state.hl & 0x0007) {

return;

}

const auto value = ExecuteBlob(state.hl, state.de);

if (value == 0xADAA || value == 0xac39 || value == 0x002f) {

const uint8_t b0 = (input >> 32) & 0xFF;

const uint8_t b1 = (input >> 24) & 0xFF;

const uint8_t b2 = (input >> 16) & 0xFF;

const uint8_t b3 = (input >> 8) & 0xFF;

const uint8_t b4 = input & 0xFF;

std::fprintf(stderr,

"[forcer] Found candidate %02hhx%02hhx%02hhx%02hhx%02hhx "

"for value %04x"

"(hl=%04x,de=%04x)\n",

b0, b1, b2, b3, b4, value, state.hl, state.de);

}

}

At this point, a few loops over all 5 character combinations of the input is all that’s required to brute force the input.

…However, I love overcomplicating things for myself for no benefit whatsoever, and instead decided to completely multithread the whole forcer for S P E E D, which allowed me to find the password in roughly 4 seconds:

$ time ./cmake-build-RelWithDebInfo/forcer 2>/dev/null

...

[forcer] iter 1073000000 (247406041.000000 its/s), eta 0m00s, remaining 741824 | 63 / 61 / 10 / 56 / 63 (64)

real 0m4,199s

user 1m43,607s

sys 0m0,185s

And the single threaded variant:

$ time ./cmake-build-RelWithDebInfo/forcer

...

[forcer] iter 1073000000 (16315918.000000 its/s), eta 0m00s, remaining 741824 | 63 / 61 / 10 / 56 / 63 (64)

real 1m5,812s

user 1m5,525s

sys 0m0,004s

There was absolutely no reason to have it run so fast as the actual forcing speed is enough to simply wait it out, but there you have it. This was tested on a Ryzen 9 5950X, so your mileage may vary depending on your hardware.

As for actually getting a proper password input out of the forcer, the candidate input values are printed while the forcer is running (and there should be exactly 3 of them):

$ ./cmake-build-RelWithDebInfo/forcer 2>&1 | grep candidate

[forcer] Found candidate 8fafb58f88 for value ac39(hl=0828,de=fff9)

[forcer] Found candidate a4a18f82a2 for value adaa(hl=1c50,de=f2eb)

[forcer] Found candidate b6b7808286 for value 002f(hl=06f0,de=0201)

Reconstructing the raw input characters and ordering the groups properly gives:

a4 a1 8f 82 a2 8f af b5 8f 88 b6 b7 80 82 86

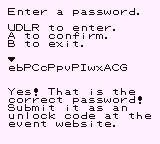

By using the Gen 1 charmap, you can convert these to actual characters to input:

ebPCcPpvPIwxACG

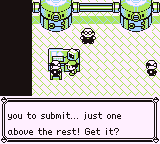

And after giving the password to the NPC:

Closing thoughts

I really enjoyed this event despite its shorter length. I got an equal amount of enjoyment as with the longer events, but without having to spend weeks blindly reverse engineering multiple different instruction sets (MIXTEST from 2023 flashbacks).

I wish I had more time to dig into the password challenge and solve it in a non-brute-force way, but real-life time constraints made this impossible; maybe I’ll revisit this one day.

Additionally, I wanted to experiment with the idea of creating a fully constexpr solver; that is - generate a C++ source file that, when compiled with GCC, solves the challenge at compile time instead of runtime.

I invite anyone crazy enough to hack away at my code and try and achieve this; I think you could automatically generate a .cpp file with a metric ton of static_asserts for each possible 5-character input group and check the adaa/ac39/002f values in the asserts themselves, so a matching input would fail compilation with an assert and you’d be able to read the solution that way.