Post outline

Welcome back to the yearly April Fools event, created by TheZZAZZGlitch. This year, we have been graced with an absolute banger of a Pokémon fan-game, which I highly recommend you check out.

Seriously, go check it out on the event website here. It’s very fun to play through, and you can really tell the amount of effort that went into putting it together. Oh yeah, it’s also Mystery Dungeon, which warrants at least 100x more points in my book.

Of course, as usual, there are also the regular CTF/hacking challenges, which is what this entire writeup is about! The challenges themselves are independent of each other, and can be completed in any order; they are not ordered by increasing difficulty (and in my opinion, the complete opposite actually applies). And as always, if you want to attempt any of these challenges yourself, feel free to do so at the event’s website, provided the site is still up.

My tools, notes and other miscellaneous stuff related to the event can be found here:

Challenge I - Hall of Fame Data Recovery (Red/Blue)

B1F is a truly amazing item. I used it to keep a small ACE payload which reminded me of my super secret password. But I encountered Missingno. in battle, and my payload got destroyed!

Think it's still possible to recover it? Here's the save file I got after the incident.

As input, we get a Red/Blue save file, which used to contain a B1F arbitrary code execution payload.

The glitch item B1F used for this is special, as using it causes execution to jump to the address $A7D0 in the SRAM, in the middle of the Hall of Fame data.

We have the B1F item in the inventory, and according to the description, the payload was corrupted.

We can verify that easily by using the item after checking Hall of Fame data in the PC (to ensure the proper SRAM bank is loaded during execution):

let’s try using B1F

let’s try using B1F

uh oh

uh oh

Clearly, the payload was corrupted and we crash.

You may ask, why was it corrupted in the first place? A side-effect of encountering MissingNo (other than bag item duplication) is the corruption of Hall of Fame data. This happens during decompression of MissingNo’s glitchy sprite, which overflows the static buffers allocated for the decompression procedure, which just so happens to be right before Hall of Fame data. The point of this challenge is then to reverse this corruption and recover the original B1F payload (hence: “Hall of Fame Data Recovery”).

Shortly after completing the challenge, YouTube recommended me this videos in my feed, which would have saved some reverse-engineering work for me when solving this challenge:

- Pokémon Sprite Decompression Explained - Retro Game Mechanics Explained

- MissingNo.’s Glitchy Appearance Explained - Retro Game Mechanics Explained

As I have limited time to prepare this writeup, and I don’t believe I can explain the concepts of sprite decompression more clearly than what was shown in these videos, I recommend you watch both of the above. I’ll still mention key things that are required for the solution, but the exact implementation will be skipped (you can always check it out in my notes repo, though!).

Oh, you’re back already? Alright, let’s start off with some very important pointers to keep in mind:

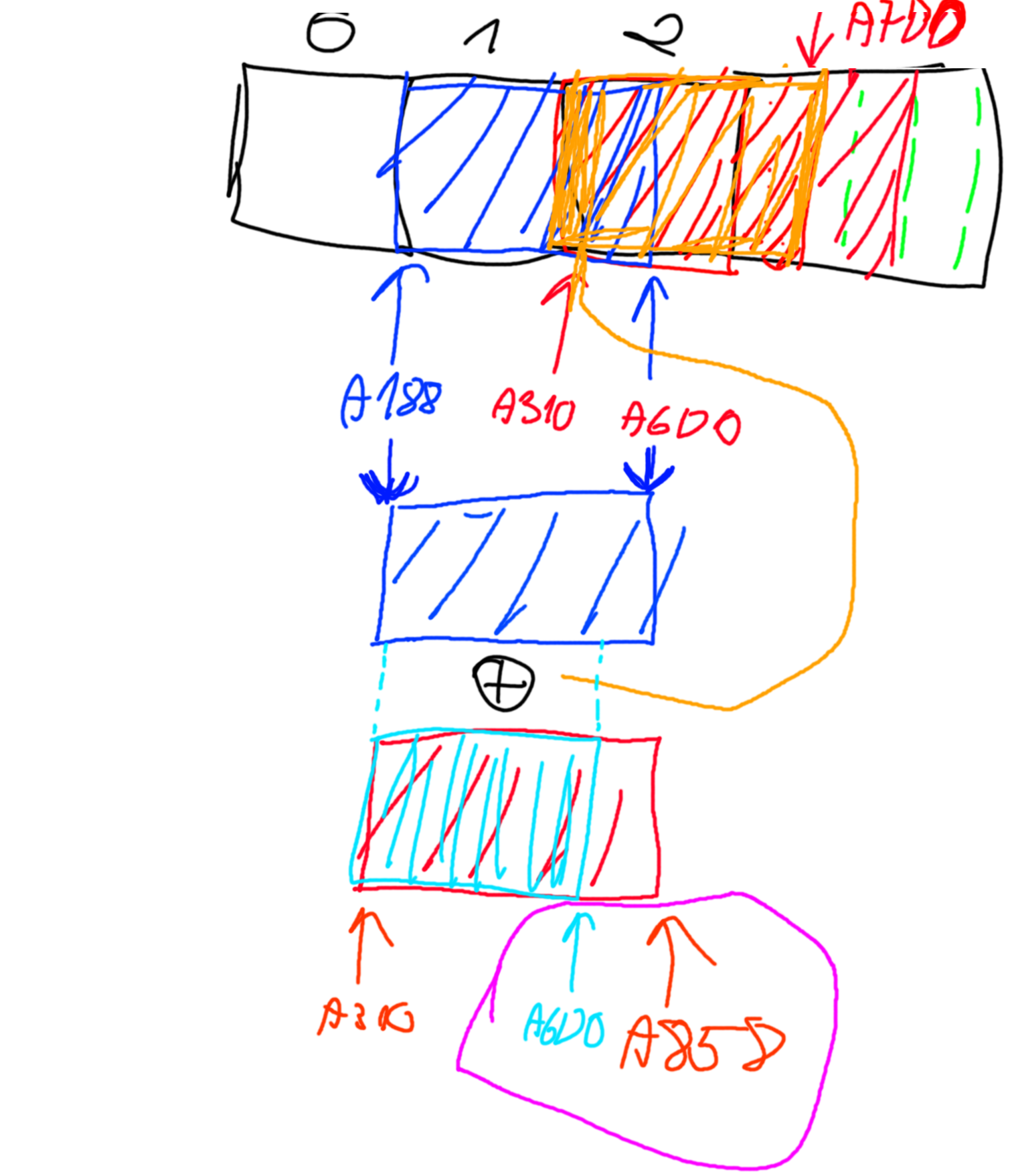

00:a188 sSpriteBuffer1

00:a310 sSpriteBuffer2

00:a598 sHallOfFame

These correspond to the two buffers used during sprite decompression, and pointer to Hall of Fame data within the SRAM region. The decompression also consists of two main steps:

- RLE decode - sprite width, height and data chunks (from

$1900) for MissingNo’s pokeid ($00) is decoded into the buffers - Unpacking / delta-decode + XOR - chunk data is then delta decoded in both buffers and XOR’d together

For MissingNo, the decoded sprite dimensions from the first step are 104x104, which results in an effective required buffer size of 1352 bytes, while the SRAM buffers can only fit 392 bytes.

Going through the steps performed during decompression of MissingNo.’s glitchy sprite and the address ranges involved, we get:

- Decode width (104), height (104), and RLE decode data into

$A188/$A310 -

Delta decode data from chunk 2 at

$A310:$A858 -

Delta decode data from chunk 1 at

$A188:$A6D0 -

XOR and store the two chunks starting at

$A310:$A188:$A6D0^$A310:$A858

To undo the corruption, we have to go from the back and apply reverse operations to each step. This is roughly:

- Re-encode chunk 1 using delta coding, to get original data from range

$A188:$A6D0 - Fix up chunk 2 corruption caused by the decoding process for chunk 1

- Bytes in the range

$A310:$A610are replaced using data from the corresponding offsets in the re-encoded chunk 1 (the chunks overlap) - Bytes in the range

$A6D0:$A858are replaced from the result of XOR’ing both original chunks together, and taking all bytes starting from offset$3C0in the XORd buffer

- Bytes in the range

- Re-encode fixed-up chunk 2

If you’re confused, here is a very rough (made in 5 minutes during the event) sketch of the layout of the two chunks in memory and why this needs to be done this way:

You can see the delta encoder/decoder, save fixer and tests in the tools/missingno directory of my tools repo.

The solution script is tools/missingno/sandbox.py, and it uses the savefile from the event to extract the flag.

I recommend playing around with it, as it dumps all the oversized chunk buffers between each step, and it’s easier to visualize what’s going on this way.

For example, here’s a dump of just the XOR operation between both of the original overlapping chunks:

$0620: 33 99 cc 33 cc 33 99 cc cc cc 66 cc 33 66 33 99 | 3..3.3....f.3f3.

$0630: 33 99 33 33 33 33 66 cc cc 66 33 cc 99 cc 33 cc | 3.3333f..f3...3.

$0640: 99 cc 66 99 99 33 66 33 cc 99 99 99 33 cc cc 99 | ..f..3f3....3...

$0650: 33 99 99 99 66 66 66 66 99 cc 33 cc cc 66 66 99 | 3...ffff..3..ff.

$0660: 33 cc 99 33 33 99 99 33 33 66 33 cc 33 99 66 33 | 3..33..33f3.3.f3

$0670: 33 66 66 66 99 cc 66 99 cc 99 cc cc cc 99 cc 99 | 3fff..f.........

$0680: 66 33 cc cc 99 99 99 cc 33 99 cc 33 cc 33 99 cc | f3......3..3.3..

$0690: cc cc 66 cc 33 66 33 99 33 99 33 33 33 33 66 cc | ..f.3f3.3.3333f.

$06a0: cc 66 33 cc 99 cc 33 cc 99 cc 66 99 99 33 66 33 | .f3...3...f..3f3

$06b0: cc 99 99 99 33 cc cc 99 33 99 99 99 66 66 66 66 | ....3...3...ffff

$06c0: 99 cc 33 cc cc 66 66 99 33 cc 99 33 33 99 99 33 | ..3..ff.3..33..3

$06d0: aa 55 aa aa aa 55 55 aa aa 55 55 55 55 aa 55 55 | .U...UU..UUUU.UU

$06e0: aa 55 aa aa aa 55 aa 55 55 aa aa aa 55 55 55 aa | .U...U.UU...UUU.

$06f0: aa 55 aa aa aa aa 55 aa aa aa 55 aa aa 55 aa 55 | .U....U...U..U.U

$0700: aa 55 aa aa aa aa 55 aa aa 55 aa aa 55 aa aa aa | .U....U..U..U...

$0710: 55 aa 55 55 55 aa 55 aa aa 55 55 55 aa aa aa 55 | U.UUU.U..UUU...U

$0720: aa 55 55 55 55 55 55 55 55 aa aa aa aa 55 55 55 | .UUUUUUUU....UUU

$0730: aa aa 55 aa aa 55 55 aa aa 55 aa aa aa 55 55 aa | ..U..UU..U...UU.

$0740: aa 55 55 55 55 aa 55 55 aa 55 aa aa aa 55 aa 55 | .UUUU.UU.U...U.U

$0750: 55 aa aa aa 55 55 55 aa aa 55 aa aa aa aa 55 aa | U...UUU..U....U.

$0760: aa aa 55 aa aa 55 aa 55 aa 55 aa aa aa aa 55 aa | ..U..U.U.U....U.

$0770: aa 55 aa aa 55 aa aa aa 55 aa 55 55 55 aa 55 aa | .U..U...U.UUU.U.

$0780: aa 55 55 55 aa aa aa 55 aa 55 55 55 55 55 55 55 | .UUU...U.UUUUUUU

$0790: 55 aa aa aa aa 55 55 55 aa aa 55 aa aa 55 55 aa | U....UUU..U..UU.

$07a0: aa 55 aa aa aa 55 55 aa aa 55 55 55 55 aa 55 55 | .U...UU..UUUU.UU

$07b0: aa 55 aa aa aa 55 aa 55 55 aa aa aa 55 55 55 aa | .U...U.UU...UUU.

$07c0: aa 55 aa aa aa aa 55 aa aa aa 55 aa aa 55 aa 55 | .U....U...U..U.U

$07d0: 3e 64 c5 82 71 28 ff fb cb 34 c2 55 31 cb c1 ba | >d..q(...4.U1...

$07e0: 8a ee 3f 55 1b ac 27 f4 c9 10 2f 52 e0 6f 65 55 | ..?U..'.../R.oeU

$07f0: aa 55 55 55 55 55 55 55 55 aa aa aa aa 55 55 55 | .UUUUUUUU....UUU

$0800: aa aa 55 aa aa 55 55 aa aa 55 aa aa aa 55 55 aa | ..U..UU..U...UU.

The data is not correct with the XOR alone, however it’s immediately apparent that we’re going the right way, as we have a bunch of repeating patterns (presumably $FFs) around a blob of data at $A7D0, which should be our payload.

After going through the entire recovery process, the resulting fixed-up chunk 2, of size 1352 bytes, contains the recovered Hall of Fame data (as the original base address for this chunk would be $A310, starting at the second buffer).

From a quick check, it’s immediately obvious that the lost B1F payload is there (the base for this dump is $A000):

$0640: ae 0d 09 c7 a6 c3 40 a0 00 70 f0 10 70 e1 f3 a1 | ......@..p..p...

$0650: 21 ca eb a7 8f bf aa 09 6d 6b 84 34 bc a8 84 9c | !.......mk.4....

$0660: 68 88 7c fe 3c ee 7b 90 60 26 fa 0b 07 77 ce 25 | h.|.<.{.`&...w.%

$0670: 95 3f b5 07 18 24 2c 3c 3c 38 25 15 cc 08 c7 cb | .?...$,<<8%.....

$0680: bf 8f 83 c2 81 c1 39 11 53 d0 c4 c3 a2 2d 21 27 | ......9.S....-!'

$0690: ff ac d9 16 46 8b 4f cf cb c1 81 c1 b3 31 30 32 | ....F.O......102

$06a0: 21 31 30 30 30 30 d3 13 22 90 ba c4 c5 c7 82 42 | !10000.."......B

$06b0: 43 41 c1 c0 04 0e 32 0f 01 a1 a8 f4 74 33 23 91 | CA....2.....t3#.

$06c0: 92 f2 f1 f0 93 71 5f ac 24 10 00 00 20 00 02 08 | .....q_.$.......

$06d0: 7f 7f ff 7f ff ff ff 7f ff 7f 7f 7f ff ff ff ff | ................

$06e0: ff 7f ff 7f ff ff 7f ff 7f ff ff ff ff ff ff 7f | ................

$06f0: ff ff 7f 7f ff ff 7f 7f 7f 7f ff 7f 7f 7f 7f 7f | ................

$0700: ff 7f 7f ff 7f 7f ff ff ff 7f ff ff ff ff 7f ff | ................

$0710: ff 7f 7f ff ff ff ff 7f 7f 7f ff 7f ff ff ff 7f | ................

$0720: 7f ff ff 7f 7f 7f ff 7f ff 7f ff ff 7f ff ff ff | ................

$0730: 7f ff 7f 7f 7f 7f 7f 7f ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0740: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0750: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0760: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0770: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0780: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0790: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$07a0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$07b0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$07c0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$07d0: 21 d6 a7 c3 49 3c 00 86 ae ae a3 7f a9 ae a1 e7 | !...I<..........

$07e0: 4f 99 a0 ff 96 fa b4 8e ad 98 b8 fb 90 58 57 ff | O............XW.

$07f0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0800: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0810: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0820: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0830: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0840: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | ................

$0850: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff | .......

After loading the fixed up save-file, I was able to confirm that this is the payload, and there is a call to show a message when executed. I did not run the payload (as I broke something in the process and it did not work), but instead chose to manually decode the text from the dump, which ignoring control characters gives:

Good job!

Za9W4uOnYy5Q

Challenge II - The Sus-file (Crystal)

I got this Pokémon Crystal save file from a friend, but it's really strange. Sometimes weird colored artifacts appear on the screen, and sometimes the game just straight up crashes. I'm sure there's something hidden in it. Maybe you'll be able to figure it out? Here's the save file I got.

We get a save containing a secret that we’re now tasked with discovering. After booting the game, the save file seemed reasonably unassuming, and not much looks to be out of the ordinary. We have the classic all-level-100 team, a full-dex PC and a bunch of items in the bag. I checked this first, as it’d immediately reveal any potential payloads that were stored as in-game items or PC Pokémon, however in this case there wasn’t anything that’d be suspicious.

For some reason though, the name of the player - MET - seemed off to me, and I started to investigate this further.

After locating the symbol for the player name (wPlayerName) in the pokecrystal disassembly, I dumped the bytes of the player name directly from memory, along with the following name buffers (each 11 bytes long):

wPlayerName: 8C 84 93 53 53 53 53 53 53 38 38

wMomsName : 38 15 00 11 A3 12 42 4B C3 F6 DE

wRivalName : 4E 4E 4E 4E 4E 4E 4E 4E 50 50 00

wRedsName : D0 D0 22 D0 D0 22 D0 D0 22 50 50

wGreensName: 22 22 22 22 50 50 50 50 50 50 CD

After confirming with a freshly created save file, I realized that wPlayerName is actually not terminated!

Each name is supposed to be terminated with a $50 byte, while the save file has the player, mom and rival name completely unterminated.

Displaying any of them will then use all of the bytes, right until the final terminator at the end of wRivalName.

To see what is actually printed, I compared the bytes from the names with the game’s character set, which led me to this:

wPlayerName: 8C 84 93 53 53 53 53 53 53 38 38 ; MET<RIVAL><RIVAL><RIVAL><RIVAL><RIVAL><RIVAL><RED><RED> (unterminated! ends at wRivalName)

wMomsName : 38 15 00 11 A3 12 42 4B C3 F6 DE ; <map$38><MOBILE><NULL><map$11>d<map$12><map$42><implCONT><blank>0<blank> (unterminated! ends at wRivalName)

wRivalName : 4E 4E 4E 4E 4E 4E 4E 4E 50 50 00 ; <NEXT><NEXT><NEXT><NEXT><NEXT><NEXT><NEXT><NEXT> (terminated)

wRedsName : D0 D0 22 D0 D0 22 D0 D0 22 50 50 ; <blank><blank><map$22><blank><blank><map$22><blank><blank><map$22> (terminated)

wGreensName: 22 22 22 22 50 50 50 50 50 50 CD ; <map$22><map$22><map$22><map$22> (terminated)

I probably got the map characters wrong and they’re a different control character instead, so ignore them because they’re irrelevant anyway.

At this point, I didn’t see anything immediately obvious, but the MOBILE control char definitely raised an eyebrow.

Hint, hint - this will be very relevant in a bit.

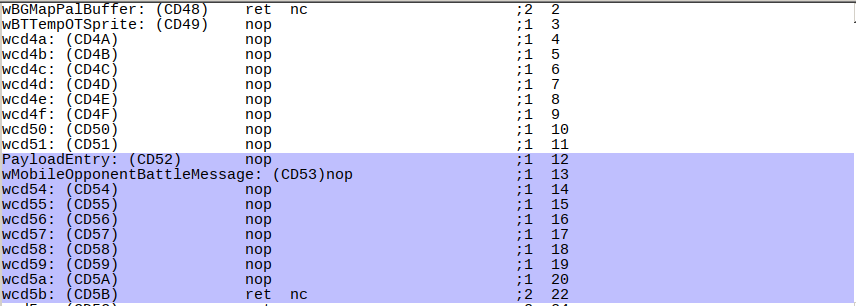

For challenges like this, I like to use bgb’s logging mode. This makes it log addresses that are executed, which is then viewable in the disassembly view. It becomes immediately visible which places are actually executed, and if any potential ACE payloads are running. For this, I did a quick scroll through RAM areas that usually are not supposed to contain code, and see if there’s a hit anywhere. And in this case, there was - a sus nop-sled was executed, right in the middle of WRAM, ending with a very suspicious return.

totally not sus

totally not sus

Putting a breakpoint there and opening the start menu hit the break!

Furthermore, looking at the stack trace, I could see that this was actually called from within a method responsible for handling mobile scripts (for GB Mobile Adapter integration).

Turns out, a MOBILE control character followed by a null byte causes an integer underflow in a function look-up table, which can then be used for ACE, which is exactly what the player name was crafted to do.

Even better, the return actually jumps into the wMomsName field, which is chained with a bunch of other data in the save file to construct a payload.

A part of this payload is shown below:

@D48B (wMomsName+??)

ld de, 12A3 ; String_Space

ld b, d

ld c, e

jp wBreedMon1Nick

@DEF6

ld a, (C590)

cp a, 79

jr nz, DF42

ld a, (C4AB)

cp a, 5 ; $DF00: $FE

; $DF01: $05

jr nz, DF42

ld a, (C51F)

cp a, 23

jr nz, DF42

@DF42

ld hl, sp+08

ld c, (hl)

inc hl

ld b, (hl)

inc bc

inc bc

inc bc

ld h, b

ld l, c

ret

(BC=C577, return to RunMobileScript, which terminates as de=12A3, [de]=$50)

The executed payload performs a series of checks against the VRAM, comparing tiles located at specific address with certain magic values. From the rest of the payload, I extracted a list of the required values and their addresses:

- [C590] = $79

- [C4AB] = $05

- [C51F] = $23

- [C4CB] = $02

- [C4CC] = $04

- [C588] = $01

I figured out the first value manually, by calculating the required tile position and manually checking for a matching tile in bgb’s VRAM viewer. This turned out to be the top left corner of the dialog box, but as we also need to trigger the payload, the dialog box would also have to contain the player’s name. The bike was a perfect choice for this - no matter if the map is overworld or a building, the resulting dialog box will contain the player’s name.

We have the whole challenge now - we must find a map/game screen, which contains the proper tiles in the correct positions. After the main checks, the payload additionally performs some sort of hash on the contents of a certain memory range, which gave me a hint that simply changing these values in memory would probably not work, and the flag is dynamically generated based on the screen data.

At this point, I thought that the easiest way to do this would be to parse map data from the Crystal disassembly and brute force all the maps to find the one containing a matching spot. You can see the result of that in tools/sus/ of my repository.

The most important script is spotfinder.py, which you can run (after providing map_data.o and tilesets.o from a pokecrystal build) to find the correct location.

Some object parsing is required (using rgbbin library, which I semi-fixed to work with newer RGBDS versions), but I found this to be a significantly better solution than doing cursed things with regular expressions.

After running the script and realizing there were no matches, I simply commented out the last value from the list, assuming that it may also be part of the UI due to it’s coordinates, leaving only the following search patterns:

- [C4AB] = $05

- [C51F] = $23

- [C4CB] = $02

- [C4CC] = $04

Running it again gave a single exact match:

SUCCESS: Found complete match at map PewterGym

In-map coordinates: 8,11 (0-indexed)

In-map coordinates (hex): 08,0b

Check 01:dcb8 and 01:dcb7 respectively for X/Y (wXCoord/wYCoord)

04 05 04 05 04 05 04 05 04 05 04 05 04 05 04 05 04 05 04 05

14 15 14 15 14 15 14 15 14 15 14 15 14 15 14 15 14 15 14 15

04 05 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 04 05

14 15 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 14 15

04 05 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 04 05

14 15 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 14 15

04 05 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 04 05

14 15 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 14 15

04 05 04 05 04 05 04 05 02 02 02 02 04 05 04 05 04 05 04 05

14 15 14 15 14 15 14 15 02 02 02 02 14 15 14 15 14 15 14 15

04 05 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 04 05

14 15 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 14 15

04 05 02 02 04 05 04 05 02 02 02 02 04 05 04 05 02 02 04 05

14 15 02 02 14 15 14 15 02 02 02 02 14 15 14 15 02 02 14 15

04 05 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 04 05

14 15 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 14 15

04 05 02 02 04 05 04 05 02 02 02 02 04 05 04 05 02 02 04 05

14 15 02 02 14 15 14 15 02 02 02 02 14 15 14 15 02 02 14 15

04 05 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 04 05

14 15 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 14 15

04 05 04 05 22 23 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 22 23 04 05 04 05

14 15 14 15 32 33 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 32 33 14 15 14 15

02 02 02 02 26 27 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 26 27 02 02 02 02

02 02 02 02 36 37 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 36 37 02 02 02 02

02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02

02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02

02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 07 08 08 09 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02

02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 17 18 18 19 02 02 02 02 02 02 02 02

Sounds promising, let’s try it out..

We’ve got the password!

Challenge III - gbhttp

The GBZ80 architecture is truly amazing - so amazing that we've created a Game Boy HTTP server! It's running at http://fools2024.online:26273/. However, we haven't done a proper security audit of our code yet. Think you can steal the secret password from our test server? The source code is available for you to review.

This is a short and sweet challenge, compared to the others.

We are given an HTTP server that is supposed to be running on a GameBoy and the sources to the service running on it.

The service exposes a few routes: /, /public, /secret, and our clear goal is to break into the /secret route by providing the right password (p) query string.

Incoming requests are passed through a harness to the GameBoy via WRAM buffers:

SECTION "WRAM0", WRAM0[$C000]

_wRequestData:

ds $800

wResponseData:

ds $800

SECTION "WRAM1", WRAMX[$D000]

wResponseHeaders:

ds $200

wResponseOutput:

ds $800

wScratchBuffer:

ds $200

wStack:

ds $100

wStackEnd:

There’s also a very interesting scratch buffer, that is immediately followed by the stack..

Theoretically, all requests are length-checked before handling, however this check is broken. Putting aside the questionable HTTP compliance, the length check is broken and putting a null byte right at the start of a “request” will completely bypass the length check, allowing an overflow from the scratch buffer directly onto the stack when the route handler attempts to URL decode the parameters of a request. We can then format a malicious request like so:

\0/secret?<INSERT_PAYLOAD_BYTES_THAT_ARE_WRITTEN_DIRECTLY_TO_THE_SCRATCH_BUFFER_HERE>

This gives us the ability to go beyond the scratch buffer directly onto the stack, allowing for code execution. We can write our payload to the scratch buffer, followed by spraying the stack with the return address to the scratch buffer.

For writing the payload, I prepared this very broken dumper:

def STATUS_INIT equ 0

def STATUS_WAITING_FOR_REQ equ 1

def STATUS_RECEIVED_REQ equ 2

def STATUS_DONE equ 3

SECTION "WRAM0", WRAM0[$C000]

_wRequestData:

ds $800

wResponseData:

ds $800

SECTION "HRAM", HRAM[$FF80]

hDriverStatus:

ds 1

SECTION "ROM", ROM0[$0200]

DumperPayload:

ld c, 255

ld de, $41F0

ld hl, wResponseData

.loop:

ld a, [de]

ld b, a

swap a

and $f

add "0"

ld [hli], a

ld a, b

and $f

add "0"

ld [hli], a

inc de

dec c

jp nz, .loop

.done:

; Notify the harness that the job is finished

ld a, STATUS_DONE

ldh [hDriverStatus], a

.forever

ld b, b

jr .forever

This utilizes the same harness that is used by the original program, but here I instead dump 255 bytes from memory starting at a given address in register de.

- Fun fact: I just realized why my automated dumper was not working with larger memory ranges, I’m dumping 255 bytes, not 256 as I assumed.

To have null bytes survive, I also apply a custom encoding that just stores each byte as two ASCII chars in the form: ‘0’ + int(nybble). The payload is manually ensured to have all relative jumps, built with RGBDS, and then manually copied as hex to the payload in the solution script.

I’m not going to post the solution script here, as it’s absolutely awful and hacked together. Feel free to check it out, alongside the dumper payload, in the tools/gbhttp/ directory of my tools repository.

Challenge IV - Pokémon Write-What-Where Version (Emerald)

I love playing Pokémon Emerald! The buttons on my GBA are really worn off, and they don't work anymore... but who needs buttons when I have a debugger and a steady hand? As long as you tell me which memory addresses I need to modify on which frames, I should be good to go!

To complete this challenge, you will need to provide a solution file, which will contain a list of memory edits necessary to complete a fresh game of Pokémon Emerald from scratch. Completion is defined as viewing the credits. For more information about the file format, challenge premises and solution verification, visit the Challenge IV: Information page.

A TAS challenge! The gist is that we are allowed to perform any number of writes to EWRAM and IWRAM (both work RAM areas on the GBA), and with this we must start the credits within 9000 frames of the game starting.

For this challenge, we can use the pokeemerald disassembly project. As a start, I wanted to familiarize myself with Emerald’s codebase and see if something is potentially exploitable. The main thing I was looking for at this point was a method to detour execution from the regular engine loop to somewhere else, so we can execute our code and possibly start the credits this way.

After some searching, I found the engine’s task system, which basically serves as a sort-of scheduler for the different tasks the game performs. Sure enough, the tasks are stored in a static buffer, and a callback pointer is stored alongside each task:

typedef void (*TaskFunc)(u8 taskId);

struct Task

{

TaskFunc func;

bool8 isActive;

u8 prev;

u8 next;

u8 priority;

s16 data[NUM_TASK_DATA];

};

Then, I quickly localized a potential function (CB2_StartCreditsSequence) that could be jumped to to start the credits scene, in an aptly named credits.c.

I wasn’t sure how much state needed to be implicitly initialized before the credits could be played, and this function seemed like it did not depend on a lot and initialized everything by itself - perfect candidate for just blindly detouring execution into it!

We can get the address of the function using a pokeemerald.map symbol file:

0x08175620 CB2_StartCreditsSequence

One important thing to note is that in this case, the address will actually be 0x08175621, as the function is built for THUMB execution mode.

Attempting to run it in ARM mode will at best cause a crash.

The lower bit of the address is interpreted as the mode to change to during a branch using the bx instruction.

With some way of executing custom code and knowing a function that will start the credits for us, I attempted to override all the func pointers for all tasks in the gTasks table:

0x03005e00 gTasks = .

This however did not bring successful results; the game would crash shortly after displaying the credits. I re-evaluated my approach of replacing every single other operation the game was performing, assuming that this probably causes things to go into a bad state at some point, and started looking for a better way of executing code.

Thankfully, there was a significantly easier method: gMain.callback1/2.

This should be way more behaved, as we’re not replacing all the tasks the game is currently running, AND it will only be run once, no weird hacks with replacing all entries of the tasks table.

Simply set the gMain.callback field to a pointer in memory, and the engine will helpfully call a function for us!

Additionally, judging by the name CB2_StartCreditsSequence, I speculated that this is exactly how it is called in the base game itself, by setting gMain.callback2 to the address of the function, which made me more confident that this could potentially work.

So, after looking up the symbol for gMain…

0x030022c0 gMain = .

And then converting the write to gMain.callback2 to the syntax expected by the challenge…

2000 030022c4 21 56 17 08

And running it using the provided checker script…

It’s working…!

…well, almost.

This did theoretically complete the game/start the credits within the required time span, however this single-write solution would not pass validation on the site. Assuming the question marks were the reason behind the failure, I started to look into how the credits determine which Pokemon to show, which it turns out uses caught Pokemon from the Pokedex.

I tried to write some caught Pokemon to the Pokedex from the script itself, however this did not seem to persist beyond a single frame, and the dex would be cleared afterwards.

As I had already found the gMain.callback pointers at this point, I opted to go the nuclear route of a hook that is run on every frame and sets the values this way (instead of having to specify them manually in the script for thousands of frames for the entire duration of the credits scene):

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stddef.h>

typedef void(*GetSetPokedexFlag_t)(uint16_t, uint8_t);

#define GSPFAddr (0x080c0664 | 1)

void _payload()

{

// bepis name

*(uint8_t volatile*)(0x03005d90 + 0) = 0x42;

*(uint8_t volatile*)(0x03005d90 + 1) = 0x45;

*(uint8_t volatile*)(0x03005d90 + 2) = 0x50;

*(uint8_t volatile*)(0x03005d90 + 3) = 0x49;

*(uint8_t volatile*)(0x03005d90 + 4) = 0x53;

*(uint8_t volatile*)(0x03005d90 + 5) = 0x00;

// national dex

*(uint8_t volatile*)(0x03005d90 + 0x18 + 0x2) = 0xDA;

// starter mon

*(uint8_t volatile*)(0x03005d8c + 0x139C + 0x23) = 0x2;

// Set some mons as caught/seen

for(size_t i = 0; i < 100; ++i) {

// set seen and caught

((GetSetPokedexFlag_t)GSPFAddr)(i, 2);

((GetSetPokedexFlag_t)GSPFAddr)(i, 3);

}

}

You can see the payload and Makefile for building it in the tools/emeraldwww directory of my tools repo.

The payload is built using devkitARM and then written and executed from $02030000, this time using the gMain.callback1 pointer.

After testing this locally, the question marks were now gone:

And this new solution was now passing validation on the site:

1500 02030000 80 b5 82 b0 00 af 1c 4b 42 22 1a 70 1b 4b 45 22 1a 70 1b 4b 50 22 1a 70 1a 4b 49 22 1a 70 1a 4b 53 22 1a 70 19 4b 00 22 1a 70 19 4b da 22 1a 70 18 4b 02 22 1a 70 00 23 7b 60 12 e0 7b 68 1b 04 1b 0c 15 4a 02 21 18 00 00 f0 28 f8 7b 68 1b 04 1b 0c 11 4a 03 21 18 00 00 f0 20 f8 7b 68 01 33 7b 60 7b 68 63 2b e9 d9 c0 46 c0 46 bd 46 02 b0 80 bc 01 bc 00 47 c0 46 90 5d 00 03 91 5d 00 03 92 5d 00 03 93 5d 00 03 94 5d 00 03 95 5d 00 03 aa 5d 00 03 4b 71 00 03 65 06 0c 08 10 47 c0 46

1500 030022c0 01 00 03 02

2000 030022c4 21 56 17 08

Conclusion

Huge thank you to TheZZAZZGlitch for organizing the event once again. This year had an incredible amount of effort put into it, and it really shows. The insane amount of work that is required to create a full-blown fangame with this many mechanics, all for a small glitch community, deserves all the recognition in the world.